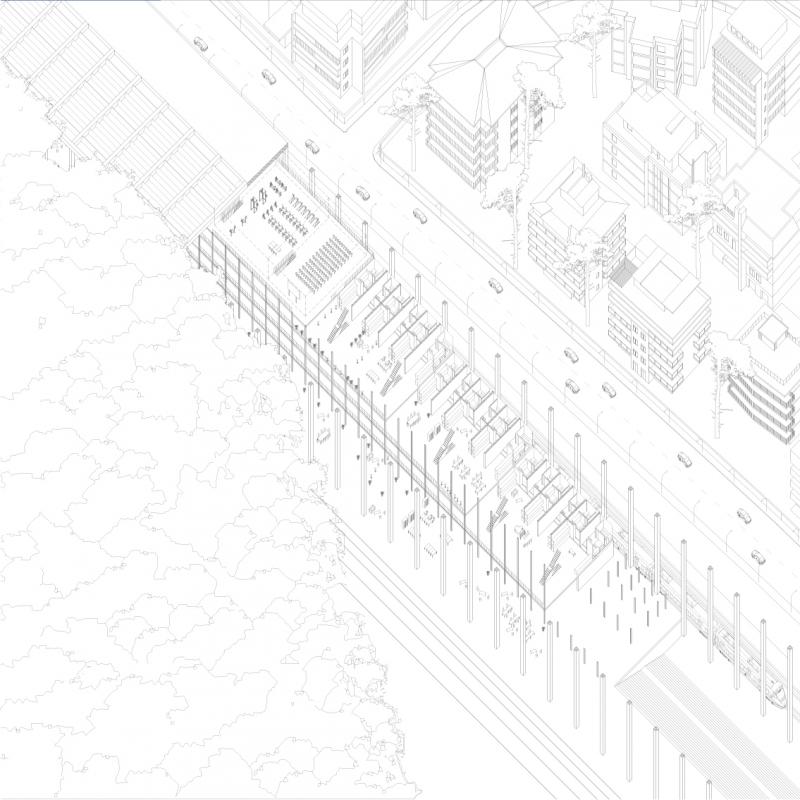

A New Grammar for the Stoa

“ It is difficult to separate public experience from so-called private experience. In this blurring of borders, even the two categories of citizen and producer fail us. (…) The contemporary multitude is composed neither of “citizens” nor of “producers”: it occupies a middle region between “individual and collective”. (P.Virno)

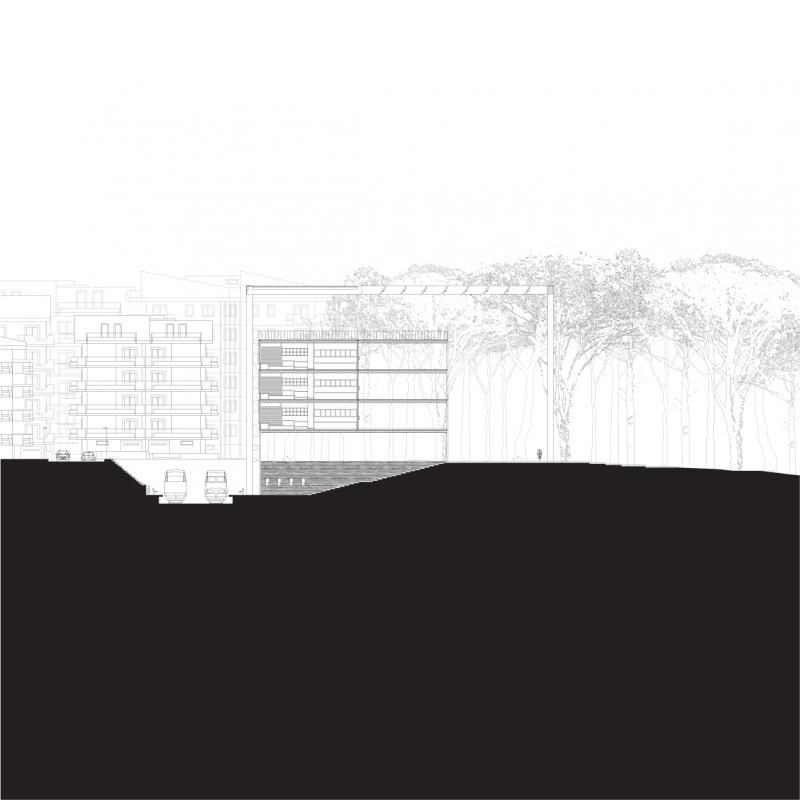

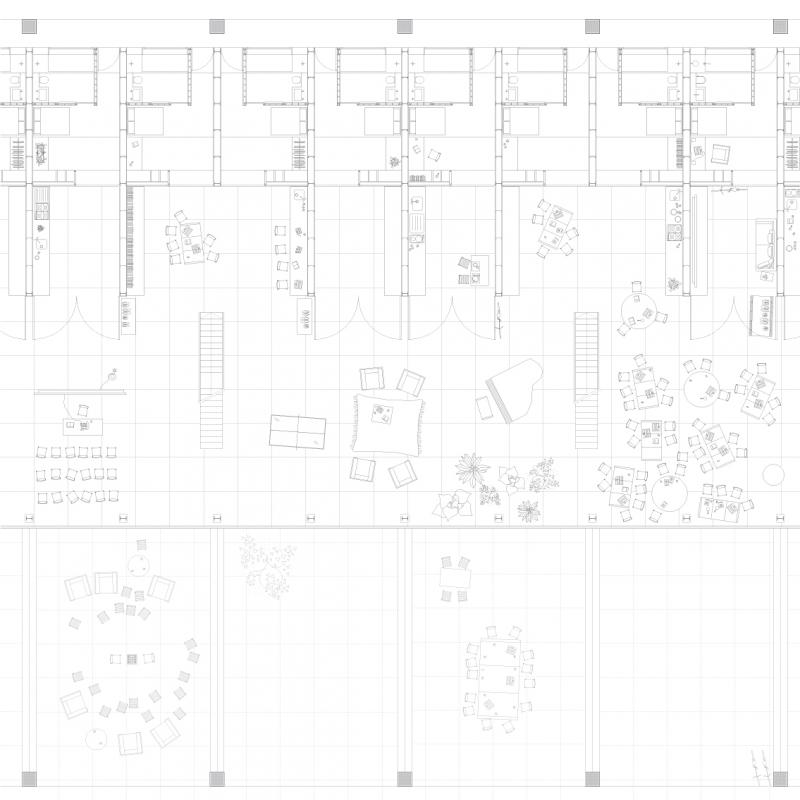

Within the project, I address this hybrid condition by articulating a space created through a series of rooms that progress into each other, negotiating between the most intimate towards the ultimate common. In this way, the traditional understanding of public and private as two segregated conditions is eliminated. As they progress, the rooms become increasingly generic allowing for uncertainty to dwell within.