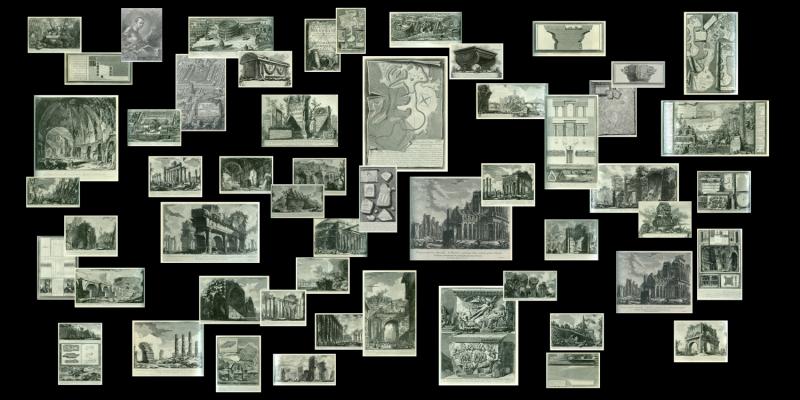

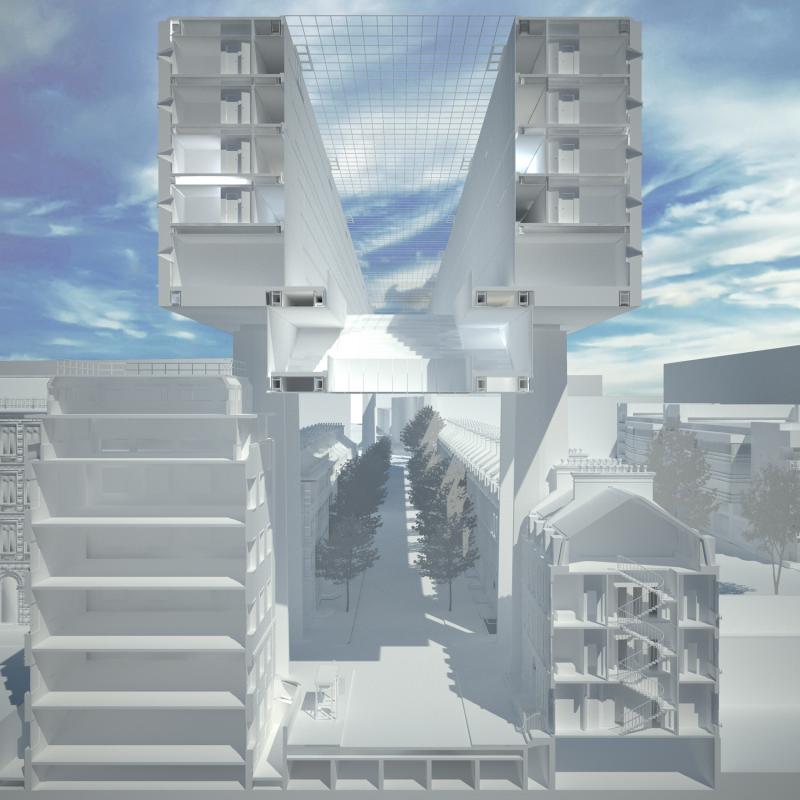

Postcard City : Travelling as Form of Collection

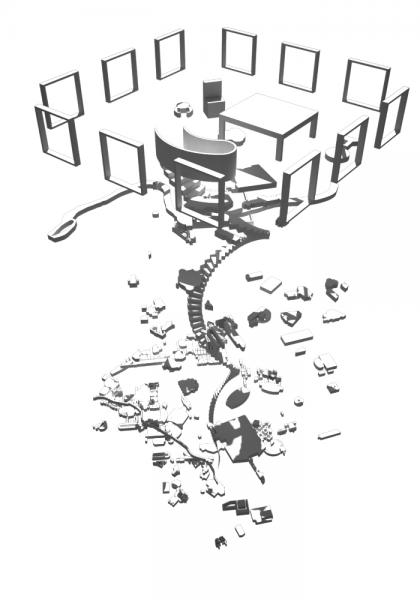

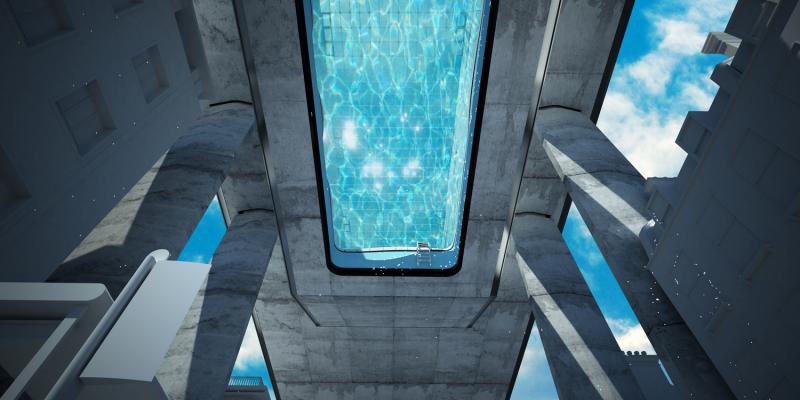

This project explores the relationship between physical construct of the city and its representative image, postcards, to experience the city not through physical entering of space but capture through other means. Political dimension of postcards lies in its profound impurity, regulated by what is chosen to be shown - or not shown, so for this instance images of the city on postcards are provocative lie. It doesn’t just keep the city in its present state but changes them, and highlight reality.